You Are Here: Engaging St. Louis’ Racial History Through Site and Story

2021-11-08 • Liz Kramer

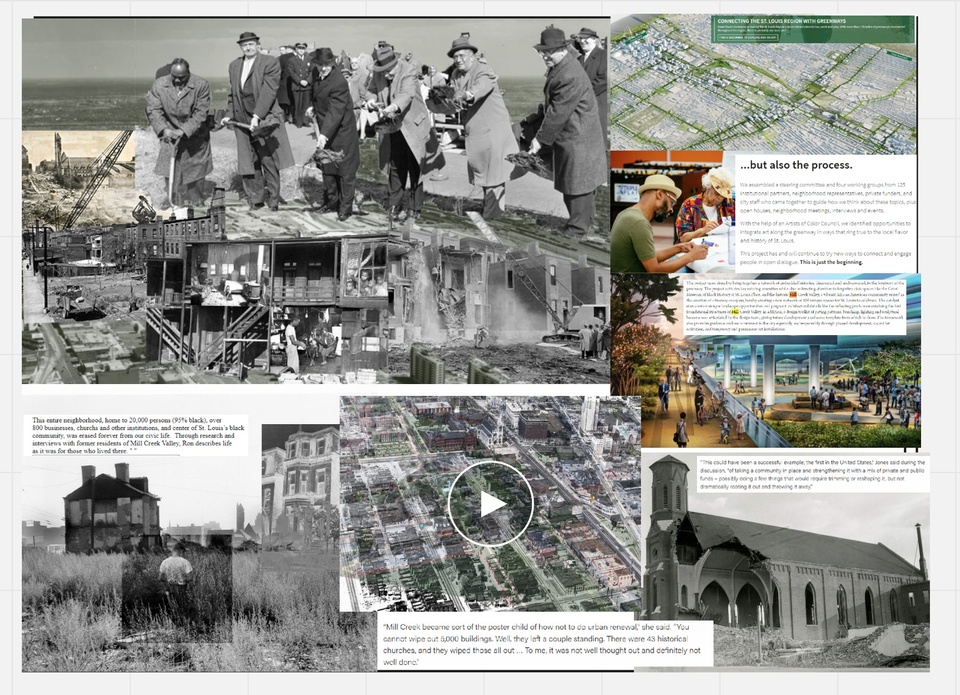

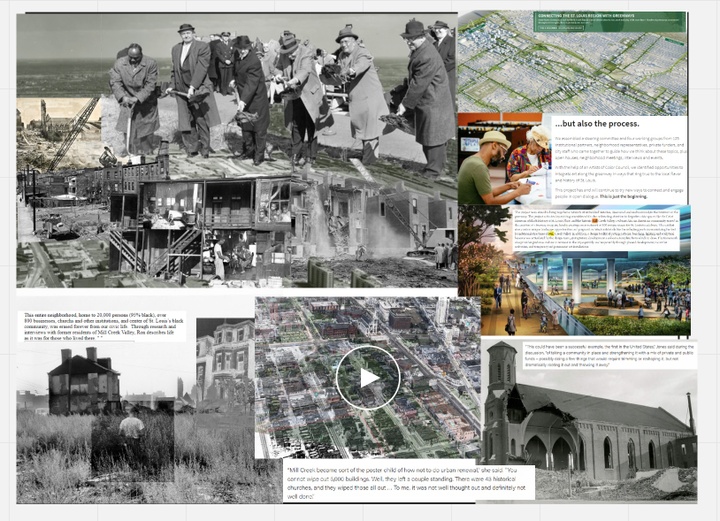

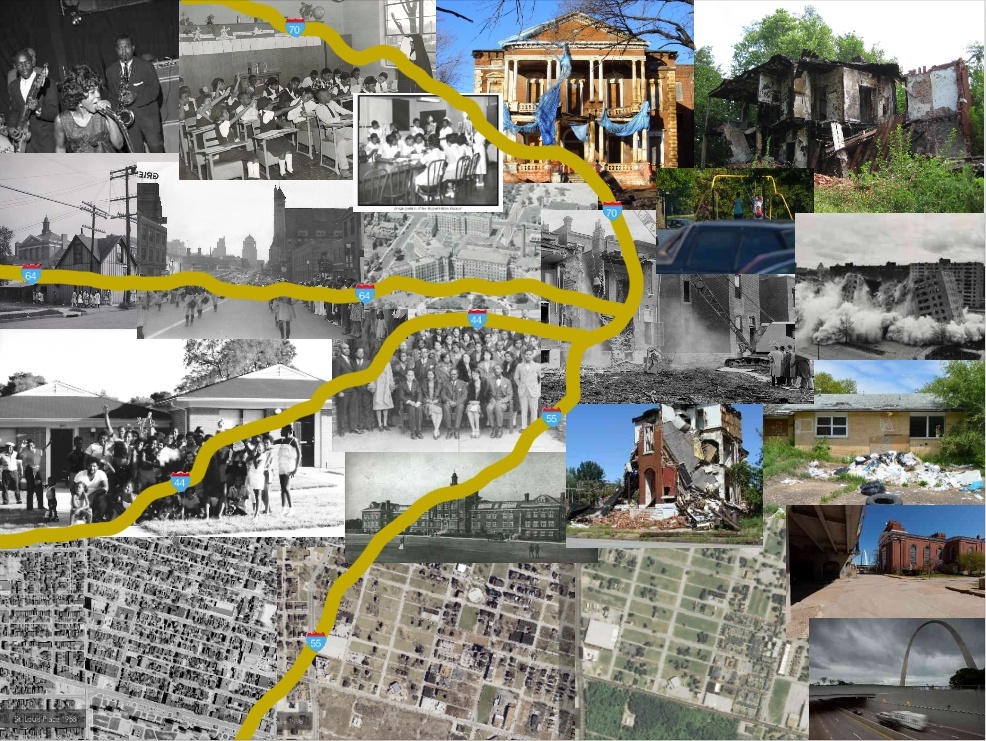

Final collage titled “Driving “Progress”: Cutting Apart Neighborhoods” by Josie Alexander.

Spring 2021 interdisciplinary seminar led by Penina Acayo Laker, Heidi Kolk, and Patty Heyda

In the 2020-2021 school year, the COVID-19 pandemic radically changed how the Sam Fox School operated, and it opened up new opportunities to address critical issues in new ways. You Are Here: Engaging St. Louis’ Racial History Through Site and Story, offered for the first time in spring 2021, was a creative and powerful outgrowth of this opportunity.

Developed by an interdisciplinary teaching team consisting of assistant professor of communication design Penina Acayo Laker, assistant professor of cultural history Heidi Kolk, and associate professor of architecture and urban design Patty Heyda, the course was created to “engage the complex history of race and racial injustice in St. Louis through site and story-based exploration.” It served as an opportunity for WashU students, particularly those new to St. Louis, to engage with St. Louis––both its history and built environment––at a time when most interactions were happening on Zoom.

The course was a response to the pressing issues of inequality and racial violence laid bare in recent years. Kolk explained that she and her colleagues proposed it not long after George Floyd was killed, feeling an “urgent need to acknowledge our nation’s long and painful history of racial division, conflict, and violence” in Sam Fox School classrooms. “In particular, we set out to design a course that highlights St. Louis’ prominent role in that long history––as a ‘Union’ city in the ‘compromise’ state, home of Dred Scott and Michael Brown, and a frequent battleground for human, labor, and civil rights struggle––histories that are not often acknowledged, and poorly understood, even by many of its longtime residents.”

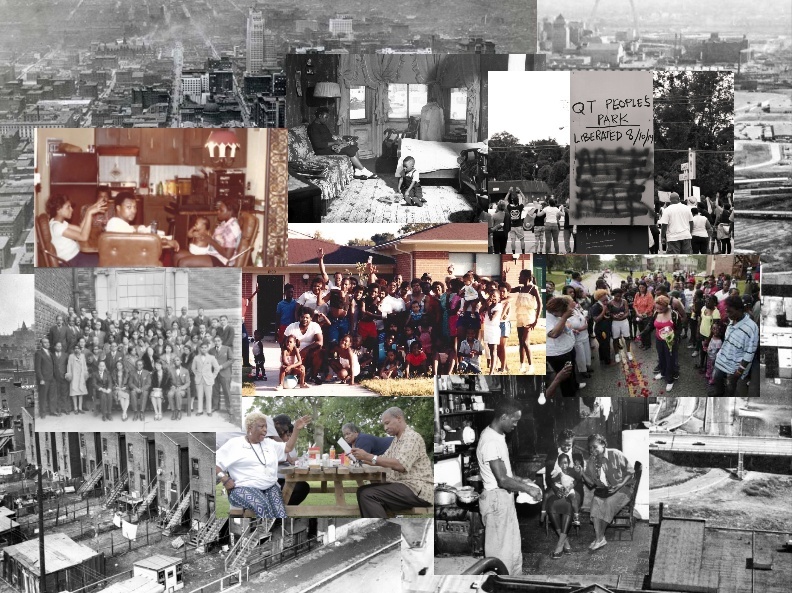

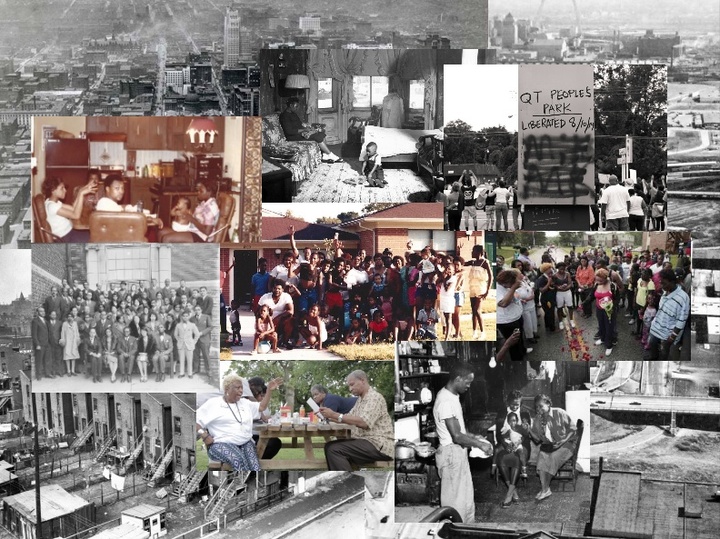

“Students in the course responded to these pressing issues,” Kolk explains, “by engaging evidence of this history in the city’s distinctive geography––with its grotesque income and health disparities and patchwork of municipalities; its ‘Delmar Divide’ and ‘WashU bubble’ and gated neighborhoods; its territoriality and aggressive policing––all products of racialized planning and development, and decades of segregation. But students also sought other points of view, other ways of seeing the city. St. Louis’ geography can also be viewed as evidence of the struggle for survival and flourishing––especially by its citizens of color, many of whom have built community and public good in spite of racial and income inequality, neglect and abuse, and repeated destruction of black neighborhoods, etc. Their efforts manifest in countless subtler features of the cultural landscape, from community gardens and neighborhood organizations to public murals and greenways.”

In each week of the seven-week course, students virtually explored a different part of St. Louis, from downtown at the Arch and Old Courthouse, through the historic Ville neighborhood, to Ferguson in North County. Based on their investigations and supporting materials, students then created a visual collage on the Miro board that captured what they learned, prompting discussion in class.

“It was particularly exciting to see how the students used visual ephemera, such as photos, video, text, and maps, to compare formal and informal narratives about the site,” Acayo Laker said. “At the end of each class session, students had the opportunity to return to their Miro board and reflect on their visual collages: identifying how their initial findings aligned or came into contention with the more official narratives and/or firsthand accounts that were discussed in class.”

“This course asked us to be much more visual than other courses, which I loved, so I often began assignments by falling down a rabbit hole of Google image searches and seeing where I ended up,” said student Josie Alexander, who is studying environmental earth science in Arts & Sciences, with minors in architecture and ancient studies. “I loved learning about St. Louis’ history, both by reading articles and looking carefully at images, drawings, maps, and photographs. Additionally, through the creation of new collages each week, I got an awesome, interesting opportunity to see firsthand how others visualize their own knowledge.”

Throughout the course, students were consistently reflecting on what they learned from the material and discussions, writing regular responses to the topics covered in class. At the end of the class, each student developed a brief that provoked the questions, issues, and priorities that resonated for them in their work as an artist, designer, architect, and citizen.

“I particularly enjoyed co-teaching with Penina and Heidi, who each brought their own approach to how to see sites,” Heyda said. “Our conversations across viewpoints exemplified the goals of the class and expanded our own thinking alongside the students. Sites—places, neighborhoods—are never monolithic, but instead made of dimensions of richly layered—contested or beloved—personal and collective stories. The class, as a site itself of different voices and approaches, continued in this spirit.”

“Taking a course like this was extremely important for me as I tried to become a more informed and engaged person in St. Louis and Missouri,” said student Rachel Zemser, a senior in communication design in the Sam Fox School. “I went into the class not knowing much about St. Louis’ history or the different communities based in the city and tried to digest and take in everything that I could. As a designer, I was again reminded of the importance of people—whether that is people that surround you, end users, or classmates. Focusing on a different community each week helped me understand the nuances of the beautiful and complex city of St. Louis that I was able to call home for four years.”

For some students, this reflection process went beyond an abstract idea. Zemser learned about the historic Homer G. Phillips Hospital through the course, and decided to take the themes and ideas she learned about further through an independent study with senior lecturer Audra Hubbell.

“With Audra, I looked at how tchotchkes, like trinkets and souvenirs, distill cities down to a singular object,” Zemser said. “Those artifacts inevitably leave out stories of what really happened and paint a glorified history of a city. Who gets to decide what story is told? What stories are neglected? How do we pick what represents a nuanced city? I looked at key destinations in St. Louis and what icons are used to represent those places. I then juxtaposed those icons with stories that are not being amplified—those stories mostly pertain to people of color living in St. Louis. Another element of this is the monetization of stories and events in history. We looked at the capitalization and commodification of cities through those icons and souvenir shops. My designs are about honoring various perspectives and considering how the prominent history is not the full story.”