Linda C. Samuels. Photo: Van Vo Photography.

Infrastructural Optimism

2022-01-18 • Liam Otten

Los Angeles’ new Sixth Street Viaduct design by Michael Maltzan Architects and HNTB Engineering was selected by a two-phase design process to replace the historical bridge originally built in 1932. The project, shown under construction in 2021, is shepherded by a multidisciplinary team under Deborah Weintraub, chief deputy city engineer of Los Angeles. Completion is expected in 2022. Photo: Gary Leonard.

In cynical times, optimism gets a bad rap.

In her new book Infrastructural Optimism (Routledge 2021), Linda C. Samuels, associate professor of urban design in the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts at Washington University in St. Louis, argues that optimism is not simply a reflexive emotional state, but a critical driver of public investment, societal progress, and—perhaps—democracy itself.

In this Q&A, Samuels discusses Infrastructural Optimism, the current political moment, and the resurgence of the common good.

You coined the phrase “infrastructural optimism” in a 2009 article for Places Journal. What was the focus of that piece?

In the wake of catastrophe, infrastructure reconstruction can be a powerful morale builder and a signal for collective optimism—as scholars like Kevin Rozario have pointed out. After the September 11th attacks, the quick resumption of public transit in Lower Manhattan, and ultimately the promise of the shiny new Calatrava transit center, signaled the city’s resilience—not just bouncing back, but bouncing forward.

After Hurricane Katrina, I was looking at how the I-10 freeway over Lake Pontchartrain, a national-scale economic conduit, was repaired ahead of schedule, while social service and public transit systems serving low-income residents nearby remained dysfunctional for years. Infrastructural investment was woefully uneven—and so was the distribution of optimism.

How do you define optimism?

Optimism is most simply the belief in a better future. There’s a distinction between personal optimism and collective optimism. Much of personal optimism comes from childhood, the support we get from family, mentors, teachers, and social circles. If every day we’re told that our prospects are bright, we tend to believe it.

Collective optimism is the idea that society has a better future on the horizon. According to cultural researcher Oliver Bennett, this partly comes from a belief in our decision-making systems—in our government, our voting processes, and the fairness of our laws. It’s a key feature in moving substantial, even multigenerational projects forward. Few people are willing to dedicate long spans of their lives to something they don’t believe in or to systems they believe treat them unfairly.

How do you define infrastructure?

I say that infrastructure encompasses the systems that support our quality of life.

I’m an architect, planner, and urban designer and tend to focus on the built environment: buildings, highways, sewers, and other physical systems. But those systems also influence, and are influenced by, social, economic, and financial systems. You can’t talk about health care access without talking about transportation networks.

So edges do get blurry, and sometimes people argue that practically anything can be infrastructure. I don’t think that’s true, either. Food is a great example. There are a lot of systems—water, soil, transportation—supporting food production. There is an infrastructure to food, an infrastructure of food, but I’m not sure that means food itself counts as infrastructure.

Despite Latin roots, “infrastructure” is a 19th-century French word that migrated to English around World War II. You note that it began to replace “public works” in common usage in the early 1980s. What’s the significance of that shift?

“Infrastructure” is logistical and tactical; its highest mission is often mono-functional efficiency, not human experience or other forms of accountability. Its operations are also often hidden from public view, which can disguise resource use.

“Public works” is social and collective, as well as enterprising and proactive. During the Great Depression, federal programs like the Works Progress Administration (WPA) responded to unemployment with highly visible public works—parks, schools, post offices, but also graphic design, fashion, and photography. In addition to providing systems that supported quality of life, they built morale and reflected a sense of collective ownership and identity.

“Infrastructure” has come to imply modern engineering efficiency. Highways are probably the best example. How do we get the most cars through at the fastest speeds with the least obstruction? But that goal doesn’t create a true public realm, and it reinforces certain biases. What is desirable for cars might not be desirable for neighborhoods. It also typically precludes interventions from architects, landscape architects, and other designers who care about experience, aesthetics, and environmental performance.

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act recently became law. What was missing from the debate about that bill?

A recognition that we’re just backfilling 75 years of deferred maintenance!

Yes, it’s a large amount of money, which we do need, and given our political dysfunction, it’s amazing anything got through. But this is not the WPA. It’s not a big collective vision. Most of the money will be distributed to states, which will largely make their own decisions. The Build Back Better Act, which remains before Congress, might be closer—if it passes.

Another thing we keep doing is dividing infrastructure into slices. Roads are here, water there, waste and energy someplace else. But these things are interconnected and interdependent. It takes energy to move water, it takes water to make energy. If we thought more symbiotically, and really considered a project’s full life cycle, we’d completely change the cost equation.

Right now, who is doing infrastructure well?

I interviewed Deborah Weintraub, chief deputy city engineer at the City of Los Angeles, about the $580 million Sixth Street Viaduct replacement. That project—which also includes a 12-acre park, amphitheater, and water harvesting—is the result of a two-phase design competition, which means it was born out of a more creative model than most contemporary bridges. The design was co-led by an architect and an engineer and brings together more than half-a-dozen city, state, and federal agencies, from Metro to Fish & Wildlife.

Those sorts of collaborations help dissolve traditional silos. Deborah herself is always asking interesting questions like: “When we dig up a sewer line, why aren’t we also putting in infrastructure for green water harvesting?” “Why aren’t we also planting trees and replacing impermeable surfaces with permeable ones?”

To me, this is next-generation infrastructure. If you’re not planning 50 or 100 years out, if you’re not thinking about multifunctionality and infrastructural symbiosis, then you’re just wasting resources.

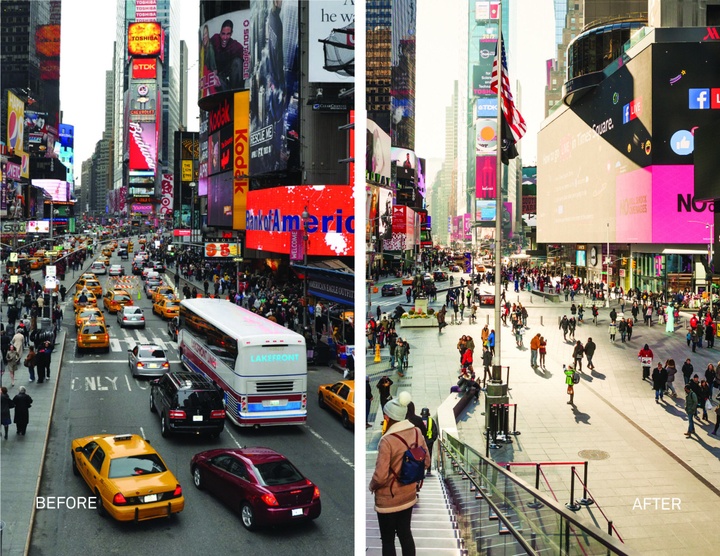

You highlight the benefits of small-scale “tactical urbanism.” What was “The Battle for Times Square”?

Former New York transportation commissioner Janette Sadik-Khan recognized that one way to change the system was to change the process. In Times Square, she used paint and $10 beach chairs to create a temporary pedestrian-only zone. Businesses worried about losing customers and revenue, but it didn’t happen. Quite the opposite. The project was a huge success and led to a permanent redesign and new plaza by Snøhetta.

Sadik-Khan also tested and ultimately added dozens of small parks and hundreds of miles of bike lanes to the city. A lot of things worked, some didn’t, but now we have a catalog of case studies and a methodology for broader experimentation. Her approach also influenced a new generation of street design manuals, which are replacing the old rigid, car-dominant guidelines.

Did COVID-19 make cities more willing to experiment with design interventions?

Definitely. A lot of parking lanes became outdoor eating and drinking spaces. In some cities—Portland, San Francisco, St. Louis—I think those changes are sticking. In St. Louis, we also temporarily closed large parts of Forest Park and Tower Grove Park to car traffic. They were packed with people walking, running, roller skating, and biking!

In places like New York, use of ride-hailing services—typically ubiquitous—plummeted, and demand for bike share and bike purchases skyrocketed. Working from home continues to gain in popularity, and office vacancies continue to rise. Real change is coming. That said, we are notoriously bad at building flexible and adaptable infrastructure.

You helped organize the national WPA 2.0 competition. What are your thoughts about the Green New Deal?

The Green New Deal (GND) gets criticized from every side. It’s too big, it’s too small, it’s too ambitious, it won’t happen. But the WPA was ambitious, too. And it happened because there was political will and a shared sense of where we needed to go. In a way, that whole project was about building national morale.

At WashU, a handful of faculty participated in the Green New Deal Superstudio, so we’ve had many conversations around the potential for designers to engage GND objectives. To me, the important thing about the Green New Deal—in addition to its forthright affirmation of the real impacts of climate change—is that it explicitly recognizes the co-dependency of environmental and social challenges, and therefore the co-dependency of their solutions. Housing, food security, sea level rise, jobs, energy production—these things are all interrelated.

I do wonder what would have happened if the Green New Deal had been introduced at a time without such massive political divides. Not that it ever was going to be easy. Big change always requires a leap.

So, how’s your optimism level these days?

I did this research and wrote this book over three presidential administrations. When I finished, I joked that my optimism had waxed and waned depending on election results.

But in truth, and as I say in the introduction, I’ve come to believe that optimism isn’t a pendulum, it’s a renewable resource that perpetuates itself. And it really will help to decide our future.