Harnessing the Power of Design

2022-03-03 • Julie Kennedy

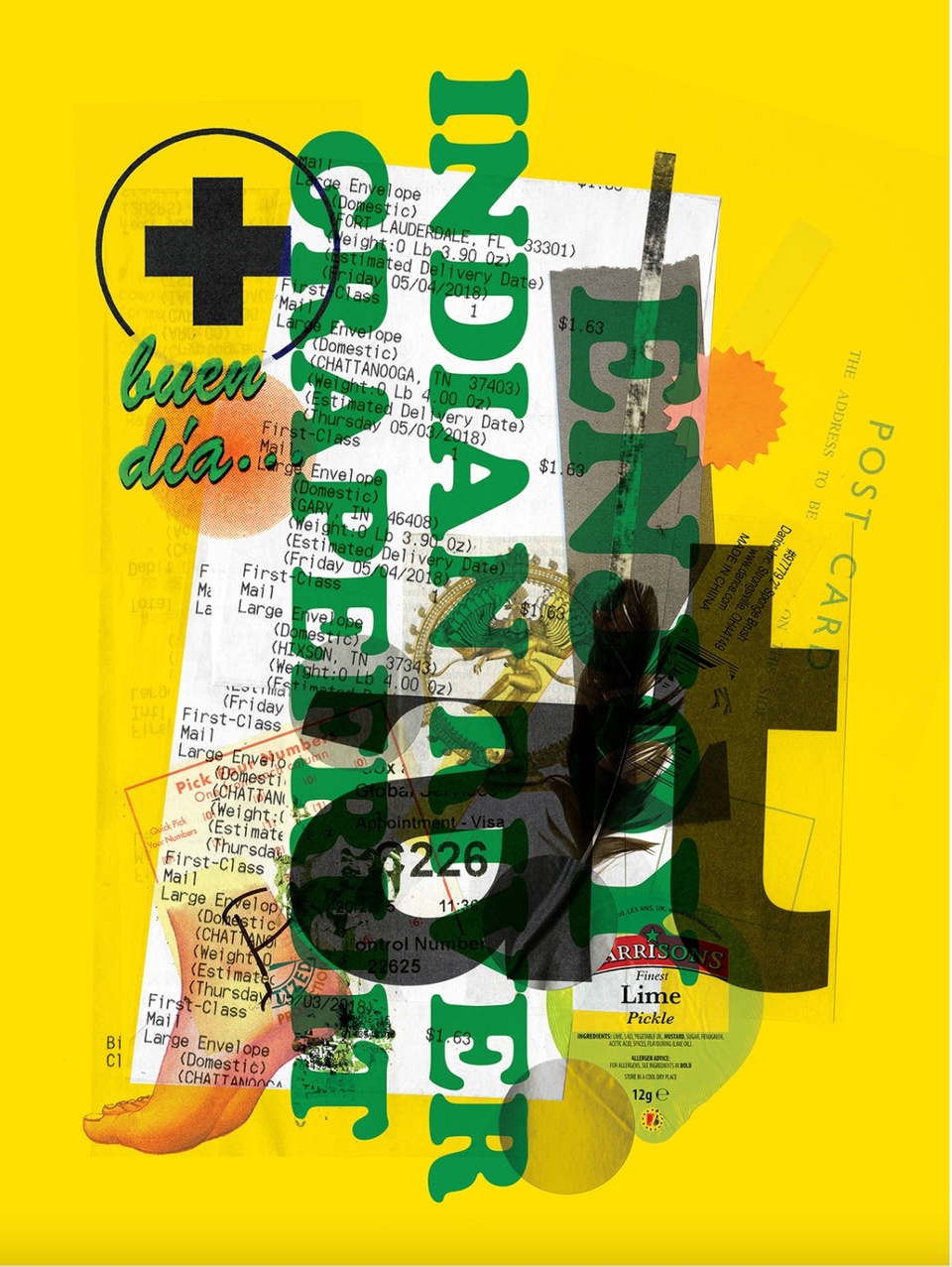

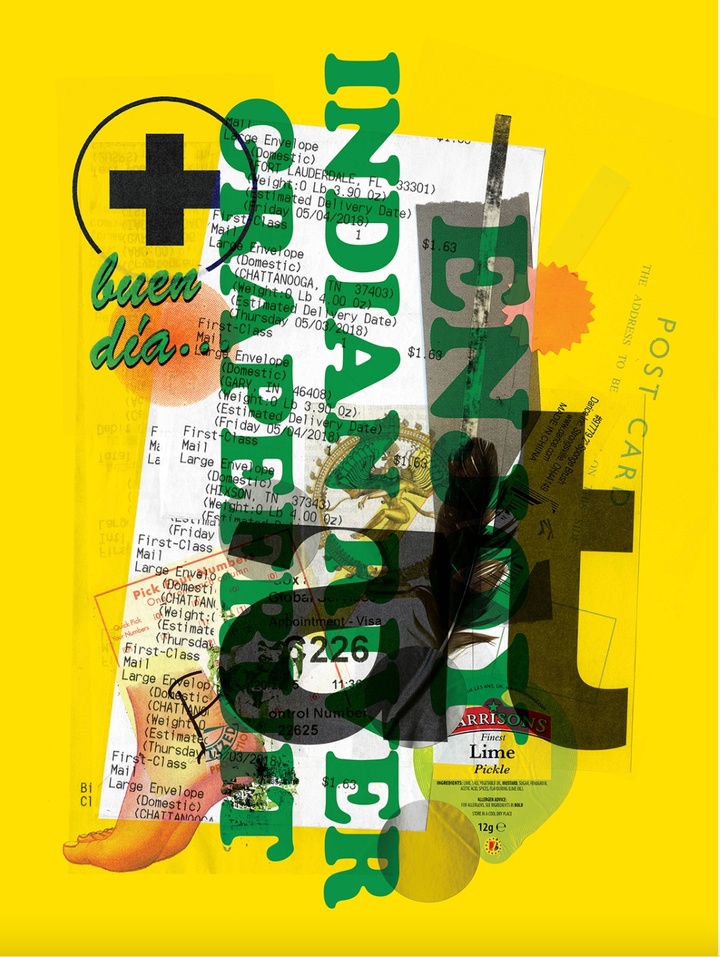

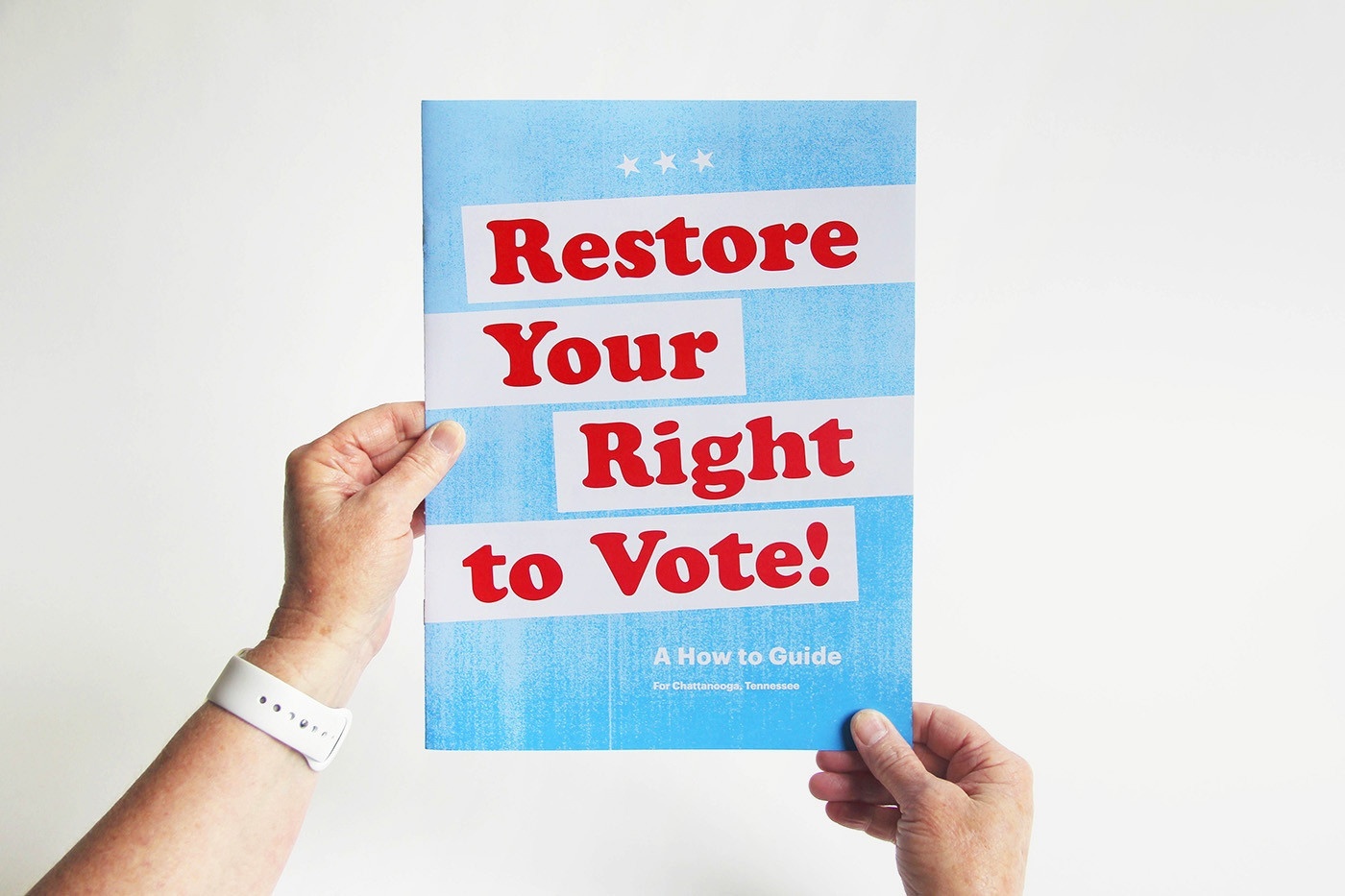

Aggie Toppins, 2017. A guide to help people convicted of felonies in Hamilton County, Tennessee restore their right to vote.

Aggie Toppins says that even though our lives are immersed in design, we barely notice the power it has over us.

“Design is the underlying structure of everyday life,” Toppins says. “You encounter design in almost every activity you do. If you go to the grocery store, you’re encountering design from the arrangement of the parking spaces to the directional signage in the store to the packages on the shelf to the way you move through the checkout line.”

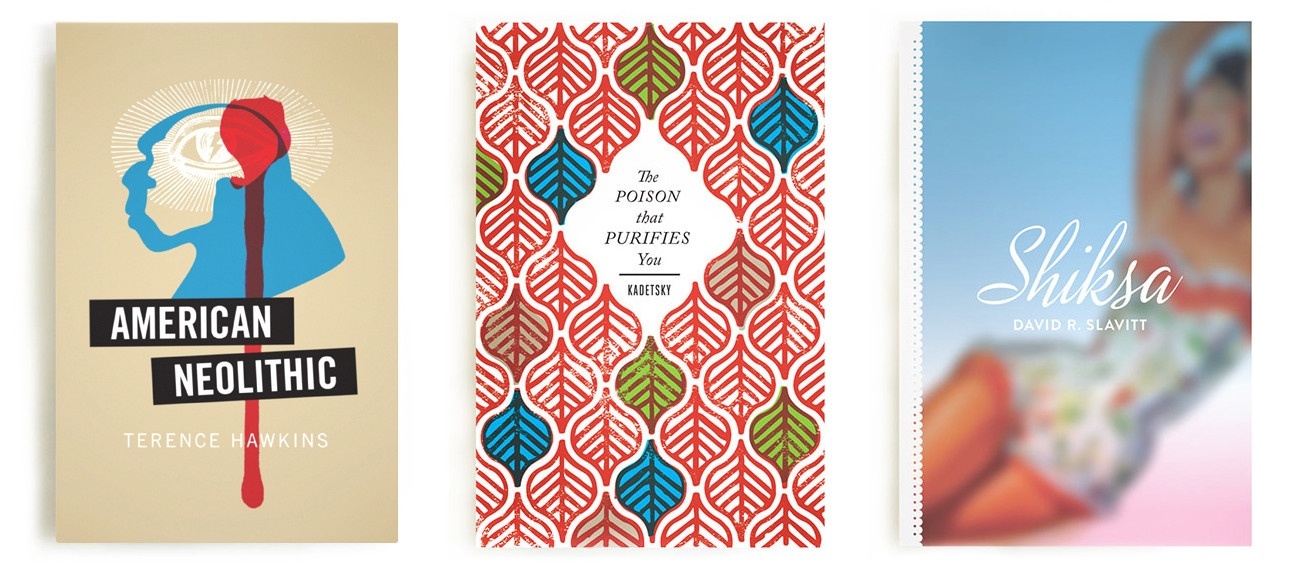

That’s why Toppins, associate professor and chair of undergraduate design in the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts, critically examines design, specifically graphic design, and its history to uncover its influence on society. Soon, she will begin writing and designing a book addressing these issues titled Thinking Through Graphic Design History. “That’s a really big achievement for me and that’s probably going to be the next three years of my life,” she says. Toppins is seeking submissions of case studies and creative prompts for possible inclusion in the book.

She also asks important questions about who has been excluded from that history, what qualifies as graphic design and who gets to call themselves a designer.

“Graphic design history was established when the field was in the process of professionalizing,” Toppins says. “But some of the most catalytic artifacts in the world were made by amateurs doing things like protest graphics. Something doesn’t have to be designed by a professional to be important.”

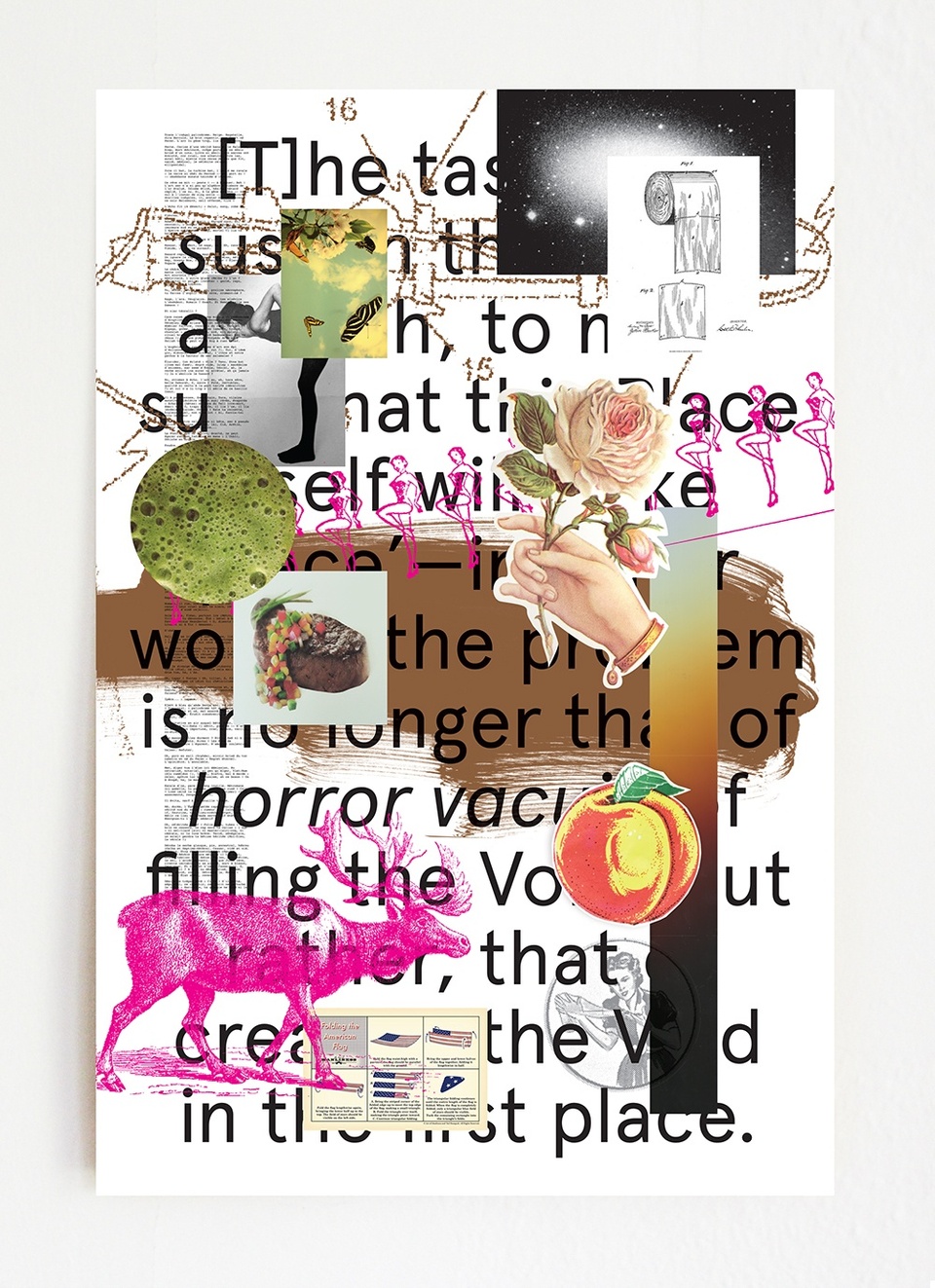

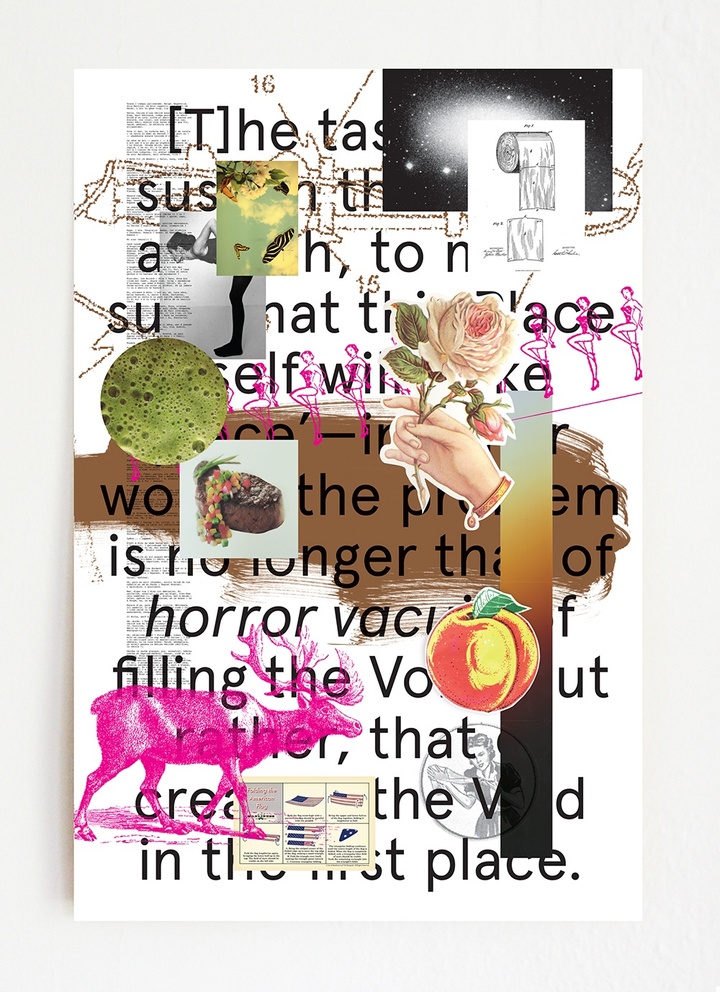

Above: TL;DR Zine Archive & Exhibition, 2021, brand identity, designed by Aggie Toppins and Shreyas R. Krishnan.

This history of exclusion is a theme that hits home for Toppins. She faced hurdles as a first-generation college student from a blue-collar background working toward her dream of being a graphic designer.

“The first week of college, I had to buy tubes of paint that cost more than any article of clothing I owned,” she recalls. “And I remember looking at this paint and wondering ‘How am I going to do this?’

She sympathizes with first-generation students because “college is a mystifying world of strange words and procedures. It’s a culture that not everybody has access to.”

She also acknowledges that being white helped advance her career but that being a woman with class struggles made her path more difficult at times. “That might be why I’m invested in social justice,” she says. “I don’t know if that’s the only reason, but I think design’s exclusions are more visible to me because of my experience.”

She notes that women make up more than half of graphic designers in the United States, but those numbers haven’t translated into equity.

“Most of my students are women, and when I was in school, most of my classmates were women,” she says. “But the interesting thing is that leadership positions are usually held by men, and women are still paid less than men.”

After 10 years as a working as a graphic designer at agencies in Cincinnati and Chicago, Toppins knew it was time for a change. She decided to get her graduate degree and enter academia. She taught for eight years at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, where she served as the first female department head in art, before coming to WashU in 2020.

“The confluence of teaching and research is really exciting,” she says. “It’s a different engagement with the field and one that I prefer. I still work long hours, and sometimes I have a lot on my plate, but I get to choose what’s on that plate.”

Toppins wants her students to understand how language and images mix to persuade and inform. She also wants her students to understand the problems and possibilities of graphic design so that they can potentially help transform the field.

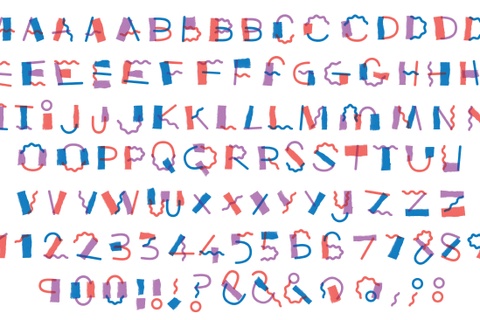

Innovation District of Chattanooga, 2016.