Q&A with Kelley Van Dyck Murphy on New Downtown Installation, “Flora Field”

2023-10-26 • Caitlin Custer

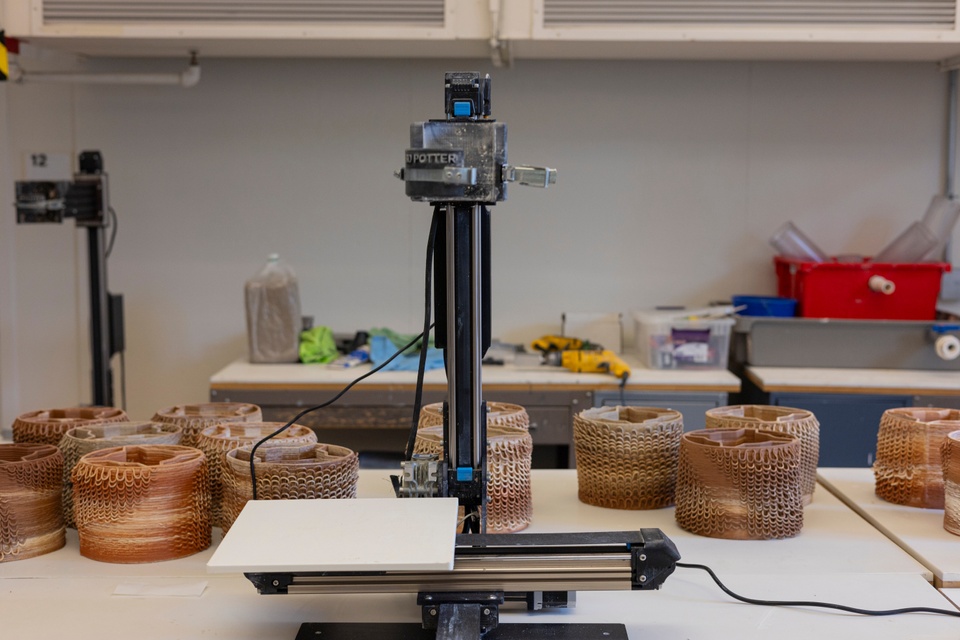

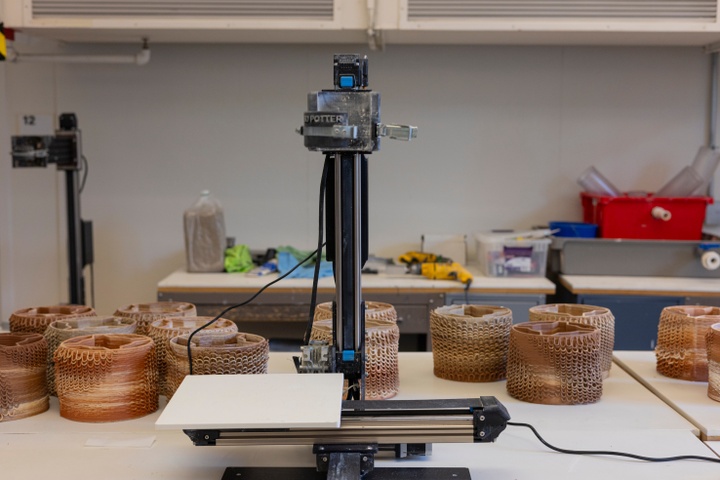

3D printed clay (Photo: Caitlin Custer)

In summer 2023, Assistant Professor Kelley Van Dyck Murphy created a public art project for installation at St. Louis’ Wainwright Building. The project stemmed from Murphy’s research in 3D-printed ceramics, and included several architecture students as research assistants, along with Jonathan Murphy, co-director of Van Dyck Murphy Studio, a WashU alum, adjunct architecture faculty member, and Kelley’s partner.

Where does the name “Flora Field” come from?

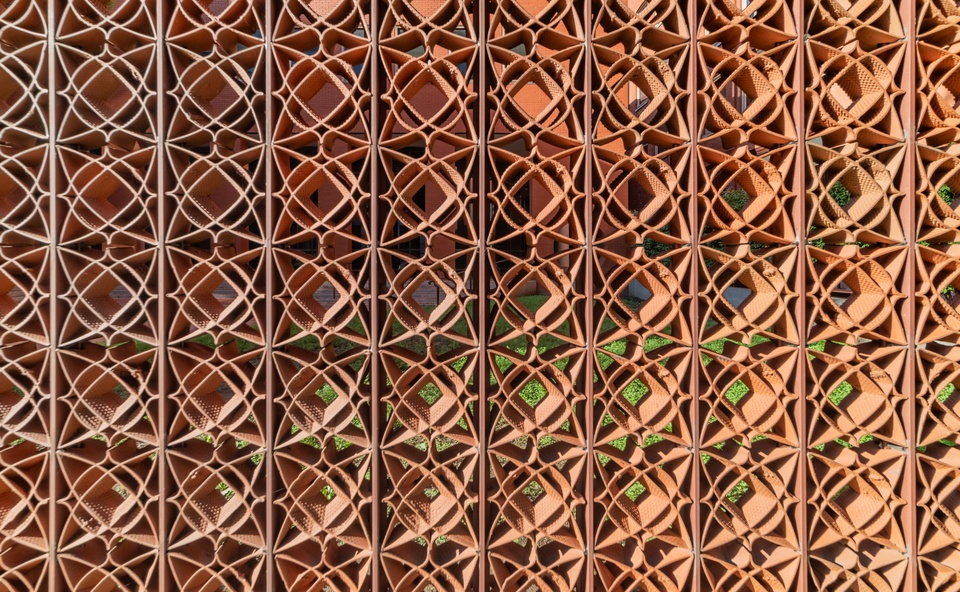

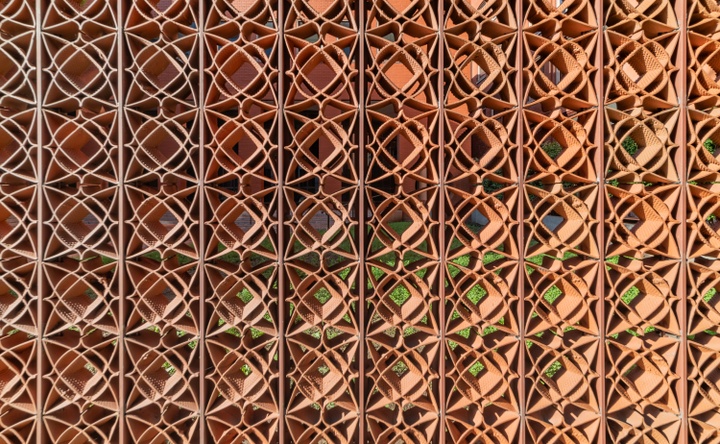

The name actually comes from the Wainwright Building itself, designed by Adler and Sullivan. The original owners were a brewing family, and the elaborate terra-cotta ornamentation on the façade of the building features motifs of hops, the flower used for crafting beer — so that’s the “flora.” The idea for “field” comes from the concept of objects and fields in architecture. This installation is a screen made up of a network (or field) of multiple related, but independent components. Plus, I like just like alliteration.

What materials are used in the piece?

The project is terracotta, which refers to both the color and the material. I really like all the terracotta color in downtown St. Louis, so we experimented with lots of different clay bodies and found one that was pretty similar in color to the Wainwright.

The project is 10 feet by 10 feet, and uses nearly 200 units that were 3D printed out of clay. The clay is supported by a steel frame fabricated by our friend Albie Mitchell, MArch ’07, and a concrete footing and base. We worked with Silman Associates, a structural engineering firm, to develop the structural strategy for the project. The easiest way to describe how the units work is like the game Connect Four. Each unit slides down the steel frame, and then they lock into a notch.

This project involved 3D printing clay — how does that work?

3D printing is an additive process with materials built up layer by layer. With all 3D printing, you make a digital model first. Then, you can use specific software to “slice” the model. Slicing allows the 3D printer to calculate the route, amount of material, speed, and extrusion rate required when printing. These calculations are used to generate the G-code, which is essentially the instruction the printer reads to build the model.

From here, you load clay into an extruder tube and a motor pushes the clay through a nozzle onto a platform. At the same time, the platform is moving to create the modeled form, texture, etc.

Working with clay has been interesting in a number of ways. First, it’s a soft viscous material, so you have to be really attentive to how the layers are extruded and stick together or you can end up with what looks like a pile of noodles. When you’re 3D printing with plastic, there will often be support printed simultaneously that can then be dissolved or broken away. You can’t do that with clay, which is how we get the really interesting textural conditions like the loops and droops that occur with no support to hold them. The extrusion is also much larger than traditional 3D printing, so the nozzle size also has potential to create beautiful textures and patterns as well.

What’s your favorite thing about working with clay?

I’ve worked for several years in 3D printing and digital fabrication, however, the material properties of clay really alter the ways these tools work. I’m trying to embrace that more in my creative process and allow for room for imprecision and the idiosyncrasies that occur in the ceramic 3D printer’s formal language.

Another great thing about clay, is that if you have a bad print, you can just wad the clay up, save it, and use it again. Recycling plastic is a newer process and it doesn’t work quite as well. Clay is something that we can reuse right away, or it can be dried, reclaimed, and reused.

How did your role at the Sam Fox School contribute to the project?

The project started because I was able to apply for a creative activity research grant through the Sam Fox School. I had taken courses in handbuilding and wheel throwing, but I was so curious about 3D printing. The grant allowed me to buy my first ceramic 3D printer, and from there it was all about experimentation.

The very first ceramic 3D printed project I worked on was for Constance Vale’s Decoys and Depictions Symposium. For the coinciding exhibition, I built a column that exposed the relationship between the digital and physical outputs, which was a theme of the symposium. The symposium and exhibition provided an opportunity to test these relationships, experiment with forms and textures, and really understand how to use the printer through a built project.

The other wonderful thing about the Sam Fox School is that we have so many amazing people who know a lot about clay. Dryden Wells, Andy Moon, and Bryce Robinson have allowed me to ask endless questions. They have a wealth of knowledge about clay bodies, what holds up in different weather, glazes, the list goes on! Their help has been vitally important for this project and my research. I’m also working with emerging technologies, specifically 3D printing with a very messy material, and that takes regular maintenance and upkeep for the machines. Matt Branham and Gregory Cuddihee have helped me diagnose printing problems and fix the printers when parts break, and they’ve provided insight about maintaining the machines so they run well.

How were students involved?

I had six research assistants for Flora Field. They were all students who had worked with me previously in my digital ceramics seminar or in my advanced architecture studios. Zach Ebbers, MArch ’23, helped us develop the grasshopper script that we used for making the final units. The script included the form of each unit, its specific texture, and the G-code — and took us the entire summer to create and prototype. Other members of our team included Fatimah Algasaff, Rosie Finglass, Nick McIntosh, Macy Morley, and Faye Hu.

The whole team helped fabricate the wall, which has close to 200 units. The students worked in shifts, and we had a schedule where we’d try to get a certain number of each unit type done each week. A few students helped when we were installing on-site in the Wainwright courtyard, too.

Your undergraduate studies were in studio art, and you earned your Master of Architecture here at WashU. How did you merge those two fields?

I see architecture as a form of cultural and artistic production and currently, I’m very interested in public art projects. This type of project allows me to test and prototype at an architectural scale, use digital modeling tools and experimental fabrication techniques, work with engineers, and engage specific sites and contexts, outside of the context of a building.

How long will the project be on site?

We have an agreement for Flora Field to stay up as long as it’s in good shape. We completed several freeze thaw tests with the terracotta when we were in the prototyping phase, but it’s a little bit of a test to see how it does in the Midwest weather.

When it comes time for us to deinstall the project, we hope to leave the concrete base and some of the steel structure for future rotating public art projects on the site.