Stephanie Syjuco

Invented Eden: Research material from the Center for the Study of the Study of the Tasaday

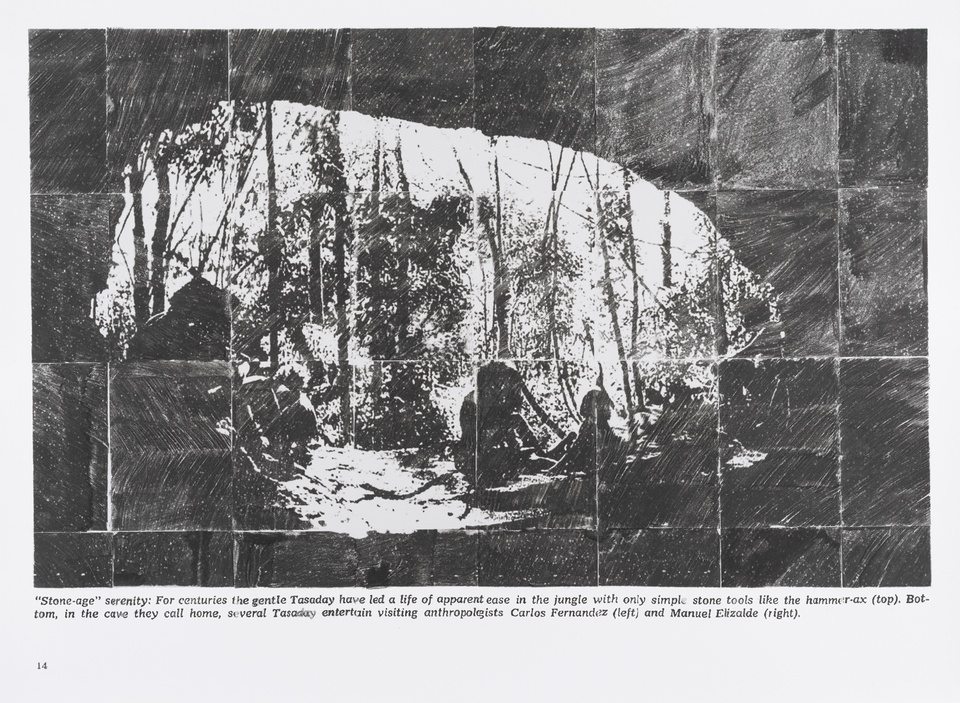

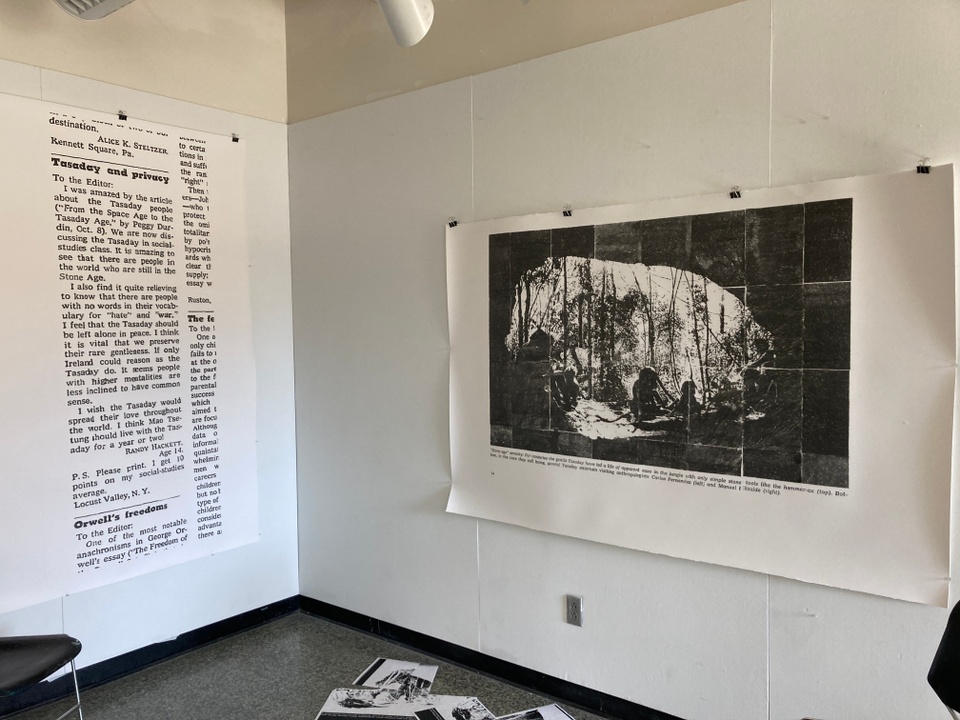

Part of an extended print series, this work focuses on photographs and documents from popular newspapers and articles about the Tasaday, a so-called Stone Age tribe “discovered” in the Philippines in 1971. By excerpting images from printed newsclippings and enlarging them to outsized, handmade proportions, Syjuco attempts to show a fragmented narrative that never quite clearly depicts the ethnographic subject itself, but instead focuses on the captions, headlines, adjacent articles, advertisements, and at times humorously ironic public sentiment that the Tasaday inspired.

This print series is part of Syjuco’s larger project, The Center for the Study of the Study of the Tasady.

PROOF essay by Thea Quiray Tagle, PhD, Associate Curator of the Brown Arts Institute and the David Winton Bell Gallery, Brown University

In 1971, scientists and representatives of the Philippine governmental agency Panamin “discovered” the Tasaday, a forest-dwelling indigenous people seemingly untouched by modernity; they quickly became the subject of media speculation and anthropological inquiry in the Philippines and globally. Just as quickly, however, the Tasaday were disappeared from public view by the Marcos regime under the guise of indigenous protection. When the tribe was contacted again in 1986– after the People Power revolution which ousted the dictator from power– they were “revealed” to be a hoax perpetrated by the government to cover its resource extraction and extrajudicial killings in the region. Over the ensuing decades, the Tasaday’s veracity has never satisfactorily been proven, yet they have remained a subject of curiosity by researchers, journalists, and artists alike.

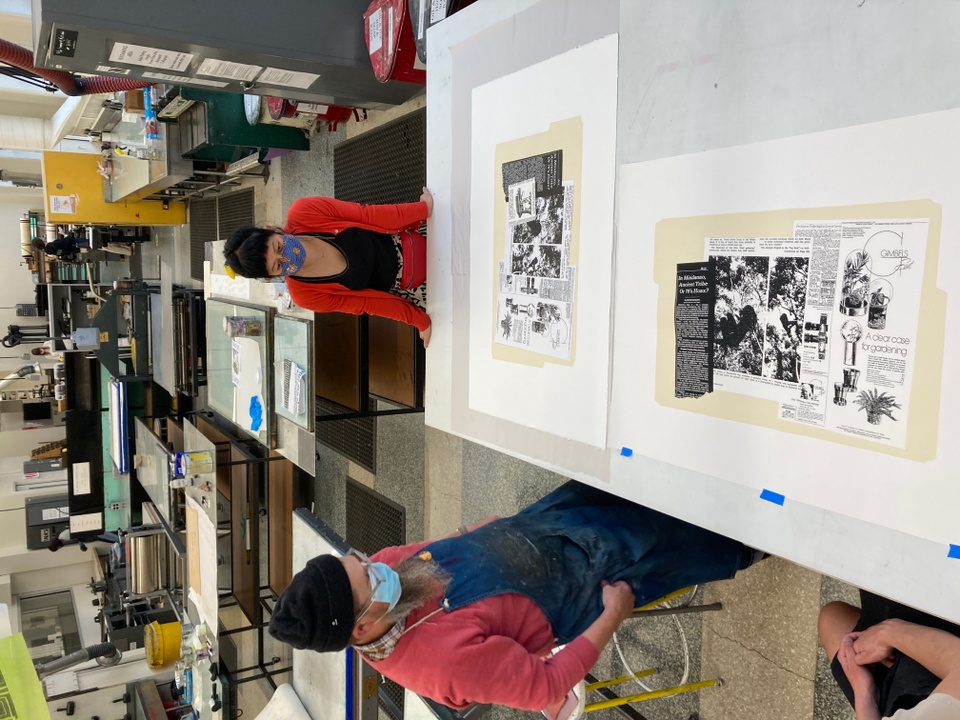

Interdisciplinary artist Stephanie Syjuco revisits the Tasaday controversy with a critical optic in Invented Eden: Research material from the Center for the Study of the Study of the Tasaday. In this series of three highly textured prints created while in residence at Island Press in 2021, Syjuco defers engagement with the fruitless debate over the Tasaday’s authenticity, and instead presents us with a meta-archive of the news clippings, ethnographic photos and documentary film stills which produced the Tasaday people as innocent primitives in need of protection from an encroaching modern world.

Her refusal to verify Tasaday indigeneity informs the aesthetic and material decisions guiding the Invented Eden prints, ironically titled Stone Age Serenity: General Clippings [CSST.005.12], This Remarkably Beautiful Photograph: 1971 [CSST.023.01], and Sensitively Filmed: 1972.3 [CSST.023.06]. First, while neocolonial discourses tried to reduce the lifeworlds of the Tasaday, Syjuco undoes this imperative by making them hyperreal and larger than life: the manila folders encasing these artifacts have been enlarged at 2x scale and printed using a CNC cut board that has been scored to look like the real thing. To play with the manipulation of information practiced by state administrators and anthropologists, the artist makes visible her own hand in assembling a counter-archive of knowledge– each folder’s contents are created through a combination of relief printing, silkscreen, hand-rubbed transfers and collage. The contents we are allowed to see are only partially visible: photographs are turned over; images are stacked and buried in a pile; and the Tasaday appear only as blurred silhouettes. Taken together, Syjuco’s methods perform a politics of Filipinx diasporic opacity reiterated in several other series produced in 2021, namely Pileups, Afterimages, Headshots (Witnesses), and Overlays, which tackle the photographic legacies of the earlier 1899 Philippine-American War and the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. Contained within the ubiquitous manila folder, the Tasaday can never be self-sovereign; yet what the artist can do is to shield their bodies from being further consumed by our western gaze.

With Invented Eden, Stephanie Syjuco extends the timeline of her probing and poetic investigations into the heart of whiteness, or the nexus where the colonial technologies of the camera, the government report, and the sympathetic white anthropologist meet to construct indigenous people from the Philippines as subjects alternately worth saving, reforming, or outright killing. From the 1899 Philippine-American War and the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, to the Marcos dictatorship of 1973-86, to the disappearances and murders of indigenous land defenders under the Duterte and current Marcos Jr. regime (all history repeats as farce), there is, unfortunately, endless material for her to excerpt from and reassemble. Placed alongside the work of other artists, scholars and activists organizing for native self-determination, Syjuco’s lens-based archival interventions make a case for indigenous peoples’ right to be sovereign over their likenesses and the very condition of their lives.

![Sensitively Filmed: 1972.3 [CSST.023.06]](https://cdn.filepicker.io/api/file/EbIEXu7SRh2vWbP7Oqlg/convert?format=jpg&w=720&compress=true&fit=max)

![This Remarkably Beautiful Photograph: 1971 [CSST.023.01]](https://cdn.filepicker.io/api/file/GJoLZuMbR5GHX4E2yDZV/convert?format=jpg&w=720&compress=true&fit=max)

![Stone Age Serenity: General Clippings [CSST.005.12]](https://cdn.filepicker.io/api/file/wa4tpMNvRjqVb40prUXZ/convert?format=jpg&w=720&compress=true&fit=max)

![Sensitively Filmed: 1972.3 [CSST.023.06]](https://cdn.filepicker.io/api/file/EbIEXu7SRh2vWbP7Oqlg/convert?format=jpg&w=960&compress=true&fit=max)

![This Remarkably Beautiful Photograph: 1971 [CSST.023.01]](https://cdn.filepicker.io/api/file/GJoLZuMbR5GHX4E2yDZV/convert?format=jpg&w=960&compress=true&fit=max)

![Stone Age Serenity: General Clippings [CSST.005.12]](https://cdn.filepicker.io/api/file/wa4tpMNvRjqVb40prUXZ/convert?format=jpg&w=960&compress=true&fit=max)